Settled Science? Or Shifting Goalposts in the Climate Debate?

Substack is overflowing with climate firestorms—catastrophists predicting imminent apocalypse on one side, skeptics waving it all away on the other. This essay isn’t here to join either tribe. I’m not trying to relitigate whether the mainstream climate narrative is broadly right or wrong (though, for the record, I have serious doubts about much of it).

Instead, let’s narrow the focus to something sharper—and harder to dodge:

Even if you accept the dominant climate premises and metrics at face value, the core policy claims have repeatedly failed when tested against reality. Each failure has been followed not by accountability, but by a quiet shift to new goalposts.

From Simple Physics to Moving Targets

The original pitch was clean and confident. Atmospheric CO₂ was the driver of dangerous warming. Cap it, stabilize the climate. Straightforward physics. Settled science.

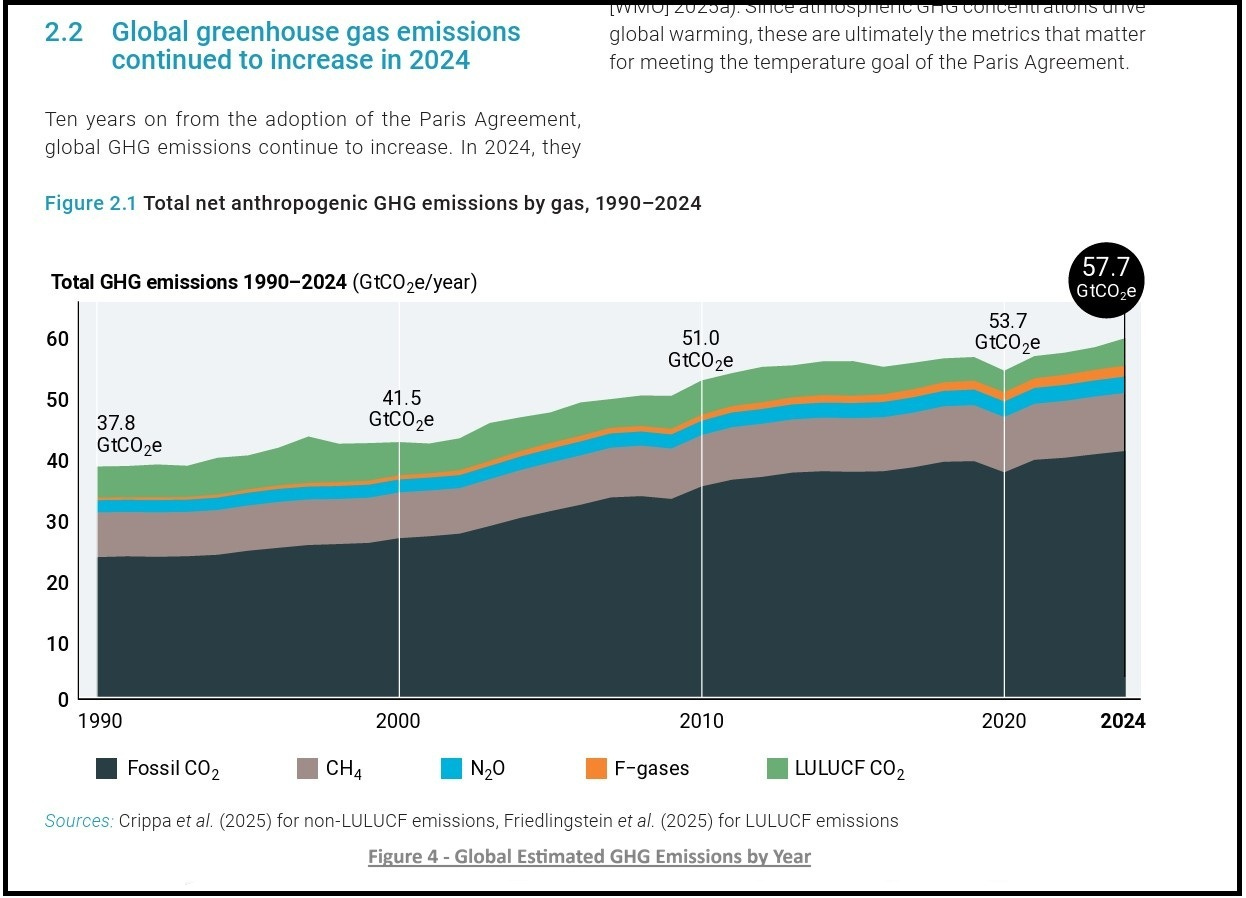

Soon, that expanded to “CO₂ equivalents”—all greenhouse gases rolled into a single metric, requiring precise annual emissions estimates. Same logic: measure it, cap it, catastrophe averted.

Trillions of dollars were spent. Mandates piled up. “Energy transitions” were breathlessly hyped.

Yet atmospheric CO₂ concentrations kept rising. Annual global CO₂ equivalent emissions kept rising too.

Reality refused to cooperate—so the targets began to shift.

When Cooling Was the Crisis

This isn’t the first time confidence outpaced evidence.

In the 1970s, major media outlets warned of imminent global cooling:

Washington Post (1970): “Colder Winters Herald Start of New Ice Age”

Time (1974): “Another Ice Age?”

Newsweek (1975): “The Cooling World”

These headlines are now mocked as pseudoscience. But a 2008 review by Peterson et al. examined 71 peer‑reviewed climate papers published between 1965 and 1979:

7 predicted cooling

20 neutral

44 warming

Science tilted warm; media hype diverged.

Sound familiar?

Ironclad Targets That Melted Away

The modern era followed a similar pattern of confidence—then retreat.

1975: National Academy of Sciences flags CO₂ warming as likely.

1988: IPCC forms.

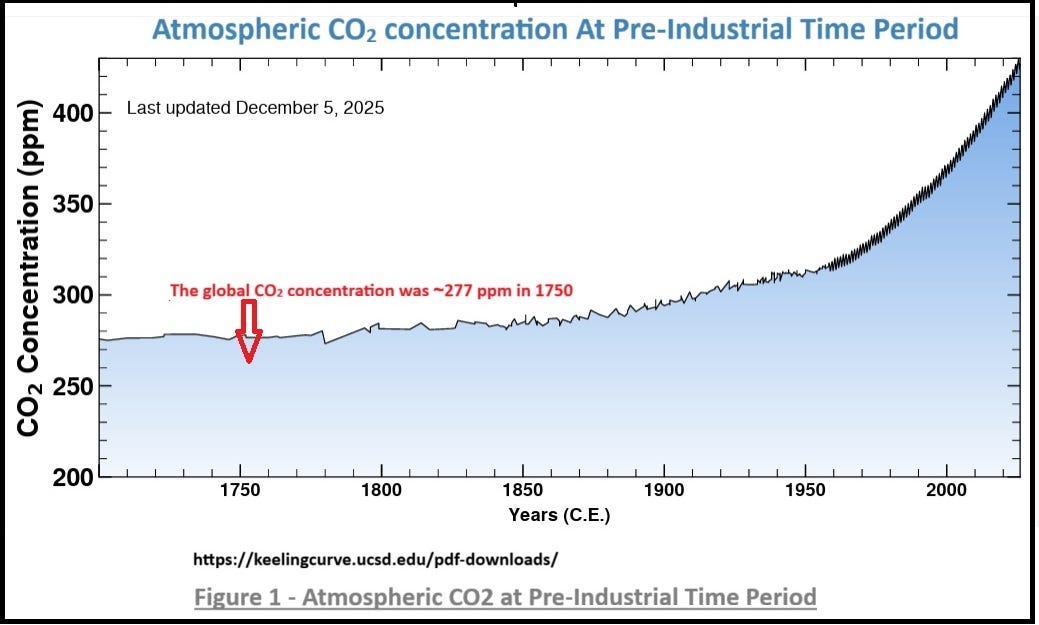

1990: First report targets ~550 ppm CO₂ (double pre-industrial ~280 ppm).

That number didn’t last.

1990s–2000s: 550 ppm remains the benchmark

Mid-2000s: James Hansen calls it unsafe

2007 (AR4): Target shifts to ~450 ppm CO₂-eqivalent

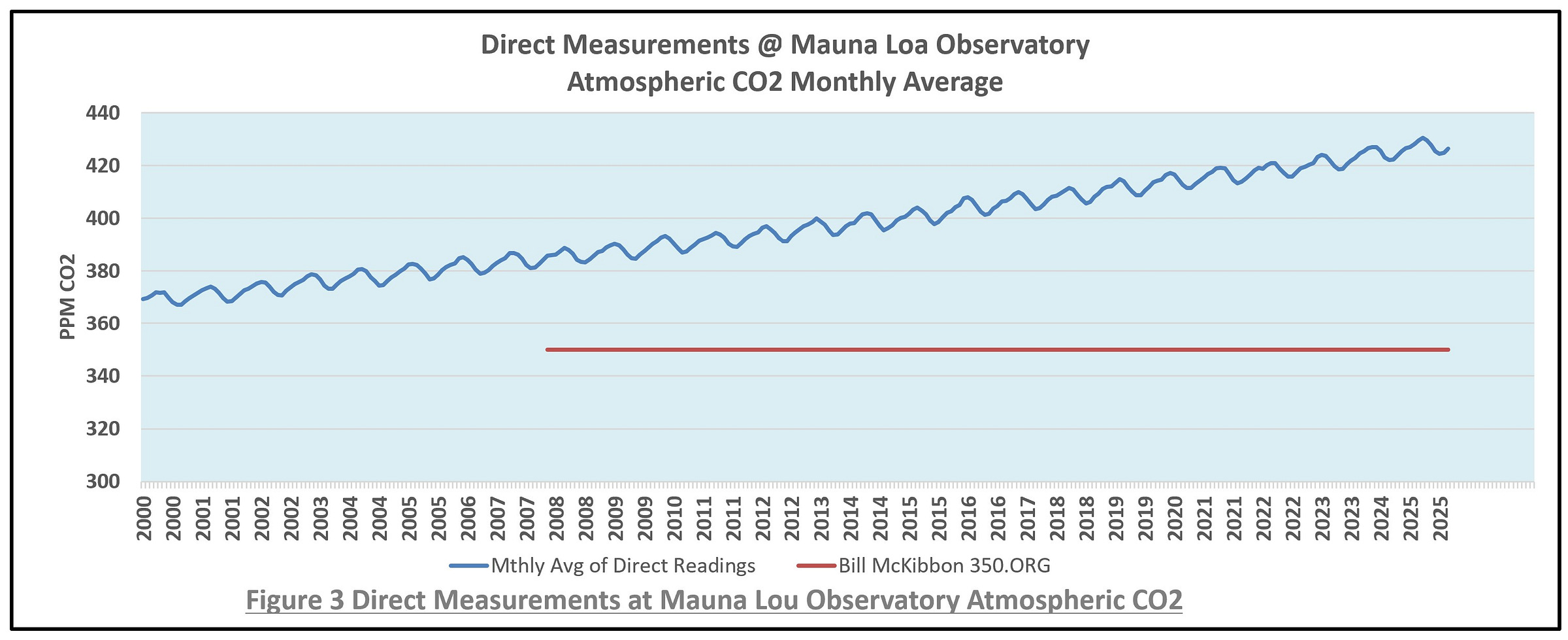

2008: Hansen declares 350 ppm the new “safe” level

350 ppm rapidly became activist dogma, popularized by 350.org:

“To preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed… CO₂ must return to at most 350 ppm.”

This was presented not as a value judgment, but as hard physics.

The Metric That Wouldn’t Behave

Pre‑industrial CO₂ was about 277 ppm.

Today, measured at Mauna Loa, atmospheric CO₂ stands at roughly 427 ppm.

Despite decades of policy, subsidies, and sacrifice, there is no visible inflection point in the post‑2000 data, below in Figure3. The curve marches upward, indifferent to our intentions.

Ask climate advocates today what the new “safe” concentration is and you’ll rarely get an answer. The old red lines have simply been abandoned.

Pivot #1: From Concentrations to Emissions

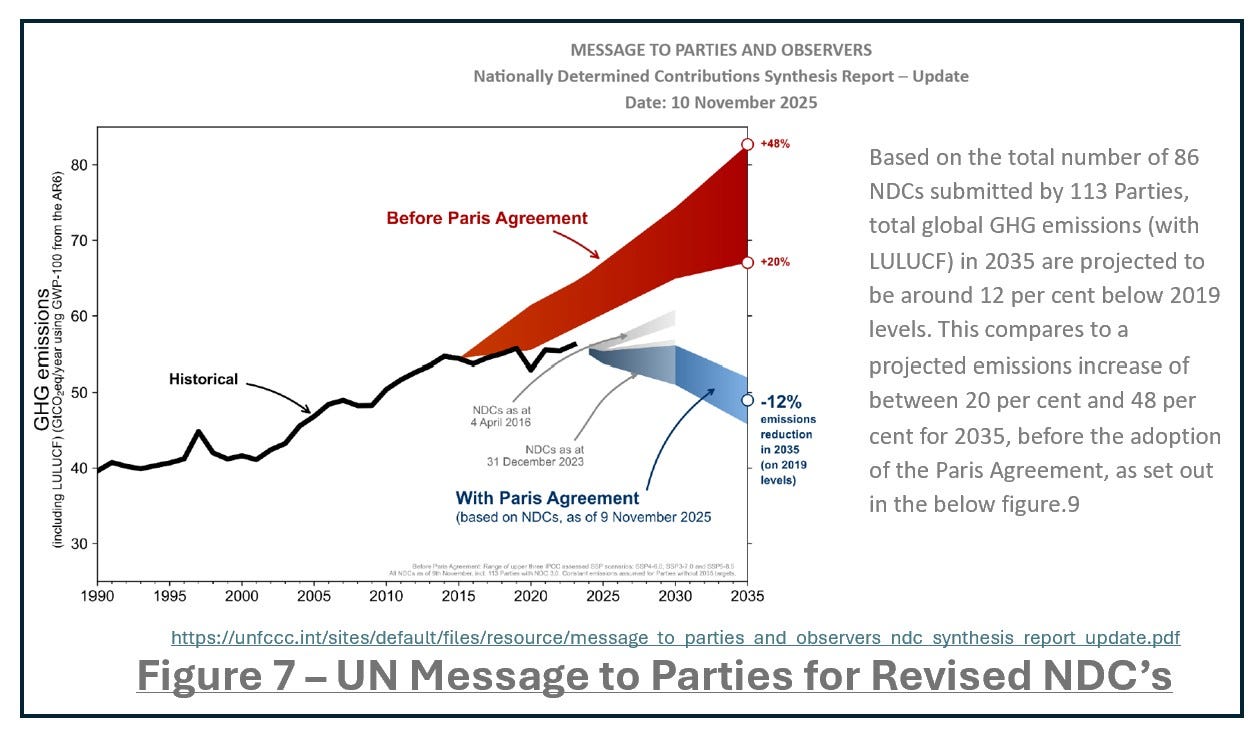

Once concentration targets were blown past, attention shifted to annual emissions. (See Figure 4 below)

But global emissions kept climbing—driven largely by developing economies. Western nations cut at enormous cost; China and India surged. The net result: new records.

Strike two.

Pivot #2: From Hard Data to Temperature Models

Around 2010, the framework shifted again—this time to temperature goals:

2°C

then 1.5°C

then “net zero by 2050”

Temperatures are politically convenient. They bundle all forcings into one number and rely heavily on models, adjustments, and projections.

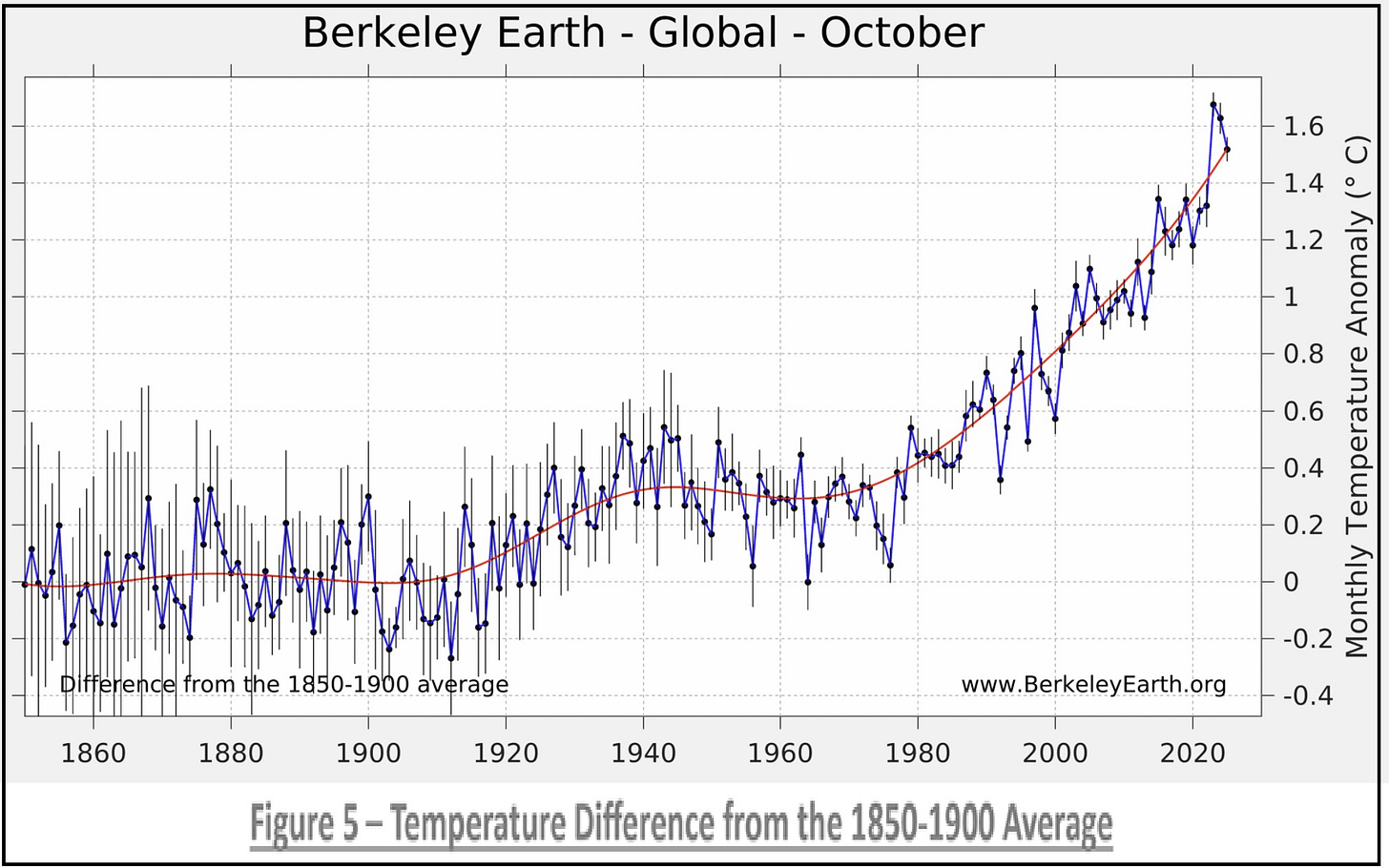

Reported global average temperature increase since the late 19th century now sits around 1.6°C (Figure 5 below)—with intense debate over tenths of a degree, while earlier benchmarks quietly disappear.

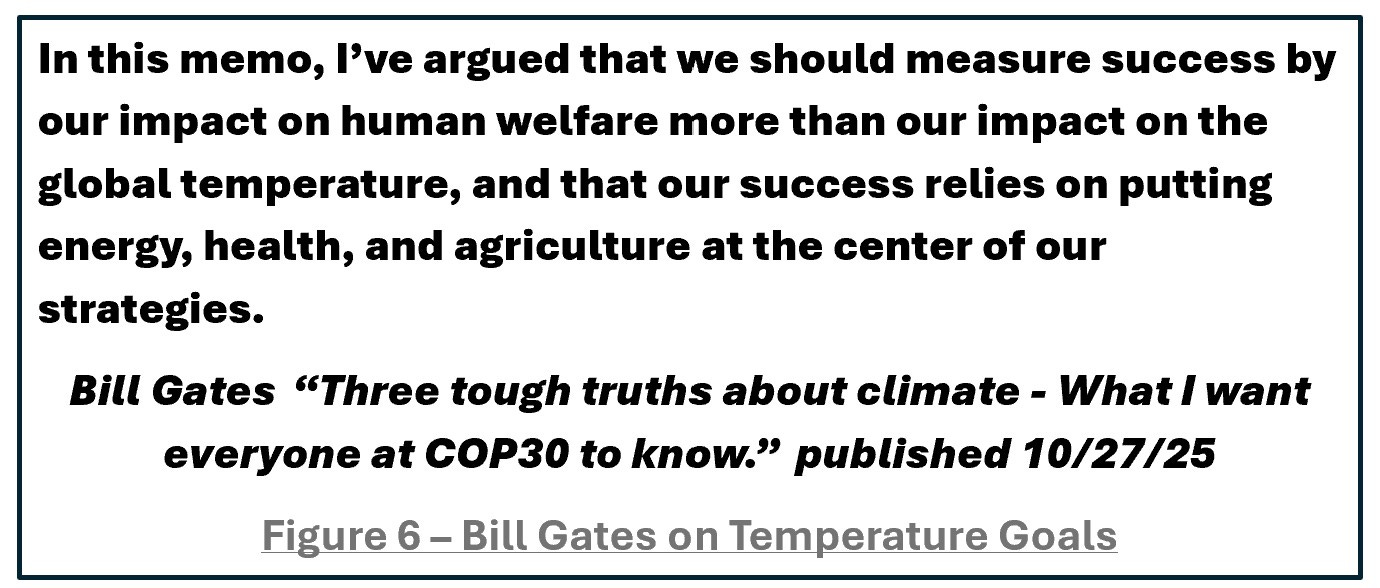

Even prominent insiders are hedging. Ahead of COP30, Bill Gates remarked that climate change is not an existential threat—and that human wellbeing should take precedence over obsessing about fractional degrees.

Victory Laps on Forecasts, Not Reality

Ahead of COP30, Gates also offered a revealing example of the new logic:

Ten years ago, the IEA predicted that by 2040, the world would be emitting 50 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year. Now, just a decade later, the IEA’s forecast has dropped to 30 billion, and it’s projecting that 2050 emissions will be even lower. Read that again: In the past 10 years, we’ve cut projected emissions by more than 40 percent.

[Note: Bill is referring only to energy emissions, not complete, just the fossil CO₂ portion in Figure 4]

We didn’t cut emissions. We cut a forecast.

UN reports increasingly celebrate “progress” not because emissions fell, but because models predict a slightly better future than older models once did. Miss your targets? No problem—update the scenario and declare success

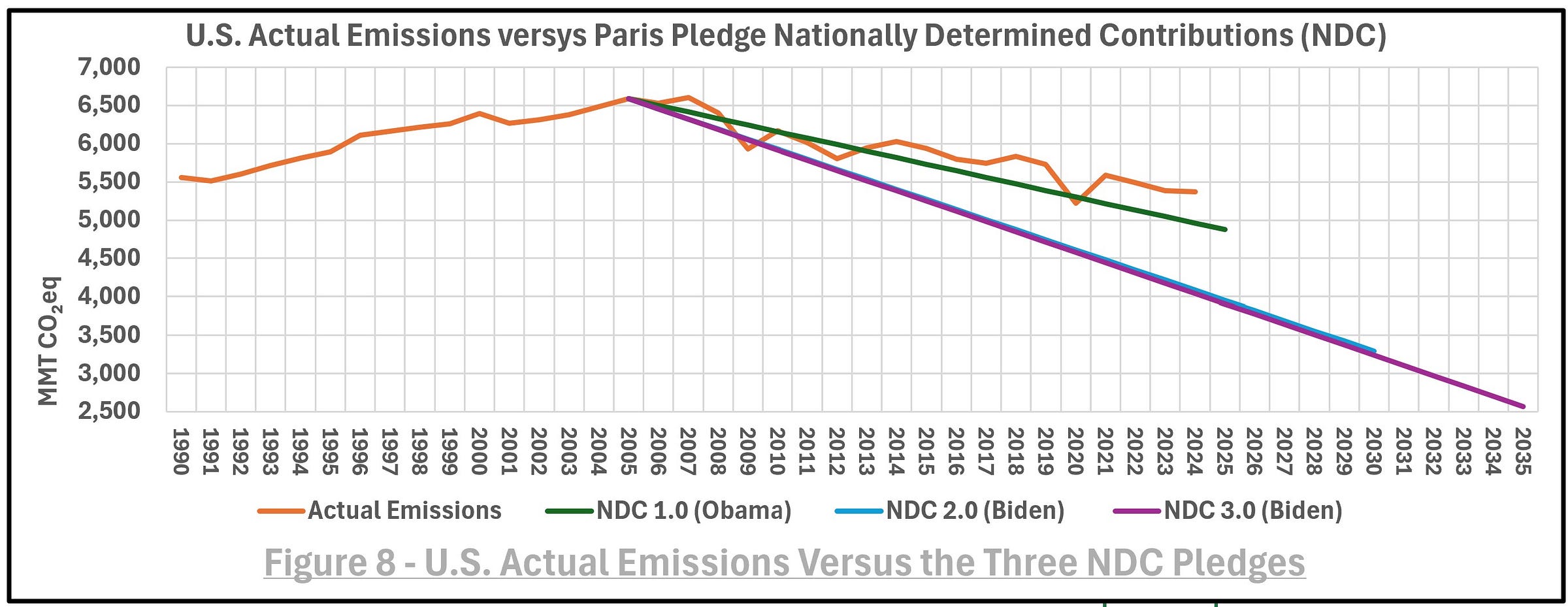

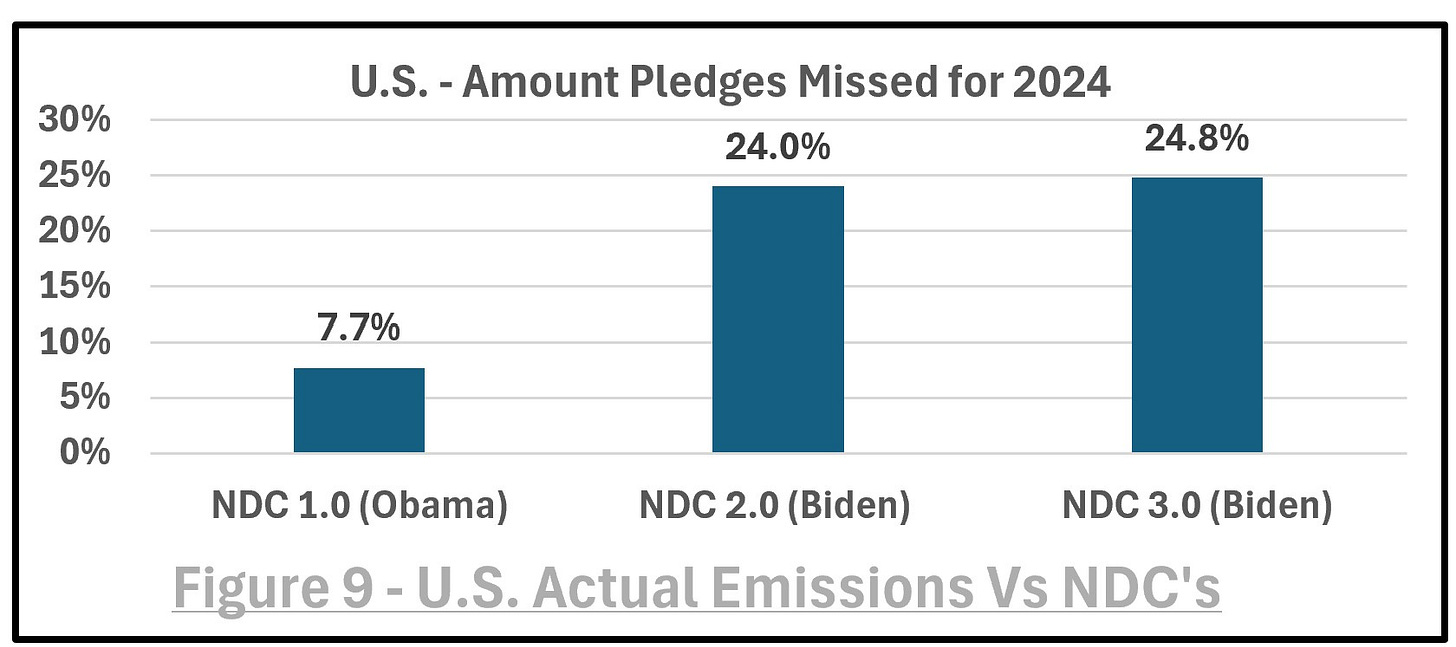

America’s Escalating Promises

U.S. climate commitments tell the same story.

Obama (2015): 26–28% below 2005 by 2025

Biden (2021): 50–52% by 2030

Biden (2024): 61–66% by 2035

Actual emissions? Down roughly 20% from the 2005 peak, largely due to coal‑to‑gas switching—not sweeping climate policy. Recent years are flat to slightly declining.

Each missed target is met not with reassessment, but with a more ambitious promise.

The Shell Game, Laid Bare

“Settled science” was sold on falsifiable, measurable claims—CO₂ concentration limits that could be directly observed.

Those limits were missed. Badly.

The response was not accountability, but metric‑hopping:

Concentrations → emissions → temperatures → models.

Each shift moves the goalposts further from hard data and closer to narrative insulation.

Important caveat: this does not prove the underlying physics is wrong. Feedbacks, lags, and complexities may explain some disconnects. The argument here is narrower—and more damning:

By its own stated metrics, climate policy has consistently failed, and the failures are obscured by redefining success.

Toward Honesty—and Effectiveness

If the goal is serious emissions reduction without wrecking human welfare, realism matters.

Wind and solar have grown rapidly—but haven’t reliably displaced fossil fuels at scale. Emissions, costs, and grid stress make that plain.

Natural gas delivered the largest U.S. emissions cuts by replacing coal.

Nuclear power remains the only proven, scalable, zero‑carbon baseload energy source.

A serious strategy would expand nuclear, leverage gas pragmatically, and adapt to realities—not chase ever‑receding abstractions.

Closing Thought

If the science is settled, it should withstand contact with reality.

What we have instead is a system that redefines success whenever the data disappoints.

So let’s ask the questions that matter:

What exactly are we measuring? What has actually been achieved? And at what cost are we chasing moving targets?

Thank you for writing this. Unfortunately I am not clear on what your objective was with this piece. It seems like you are trying to offer arguments to debunk climate change, by pointing out how stated policy objectives have failed to translate into real impact over time, as well as by pointing out how targets and objectives have moved with the decades. However, the first point is very simple in the sense that policy has not translated into impact for a variety of reasons including developing economies growing, anti climate lobbying and slow uptake of renewables. For the second point, I would expect that as science and the application of that science get refined, our understanding of what is desireable and achievable would shift. Regardless, none of these claims unfortunately in my eyes make a convincing argument for why we should stop trying to transition away from fossil fuels.

Net zero is a murderous farce.

The energy transition is the biggest lie this century.